Information and History

| Glass articles - Portobello Glassworks 1829-1968 |

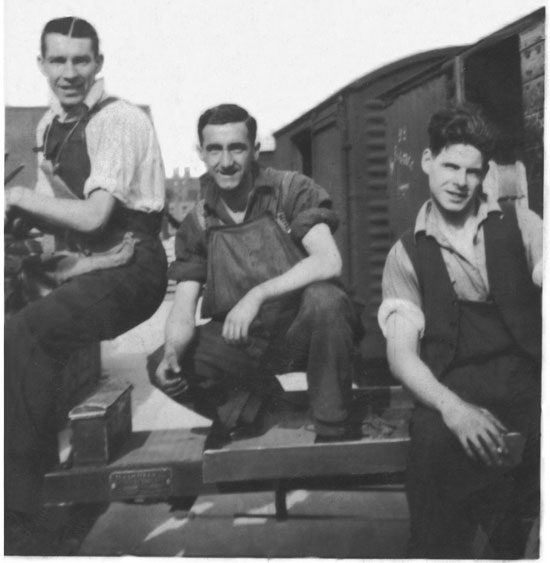

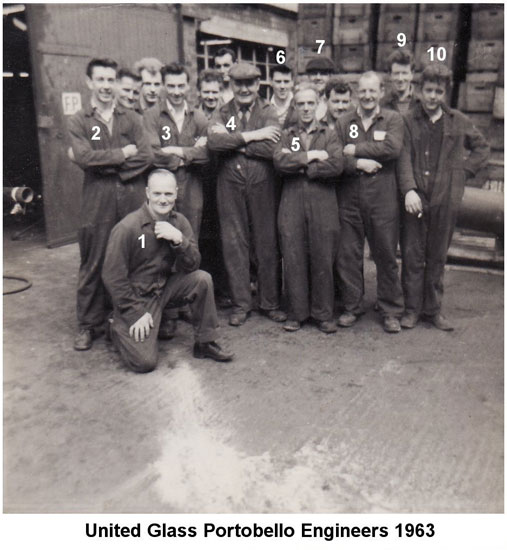

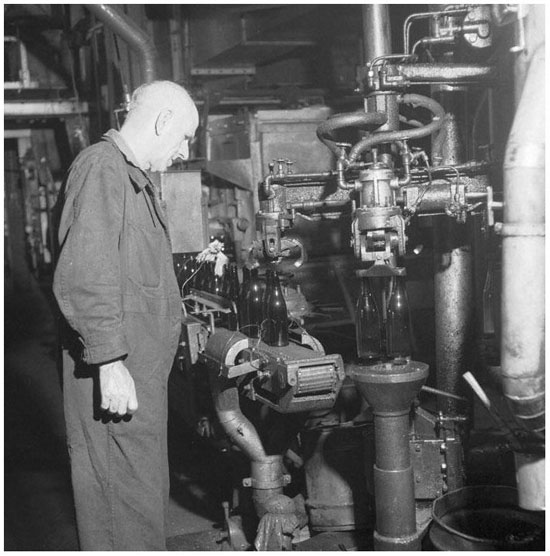

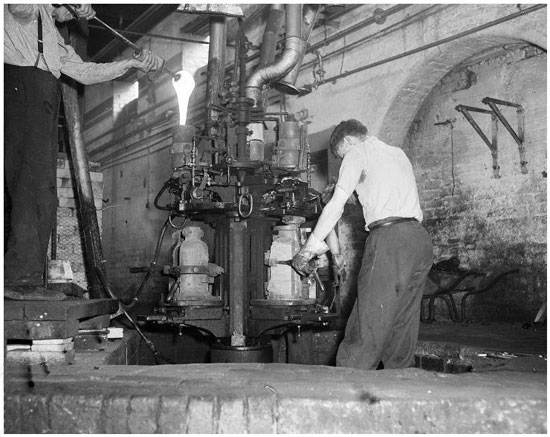

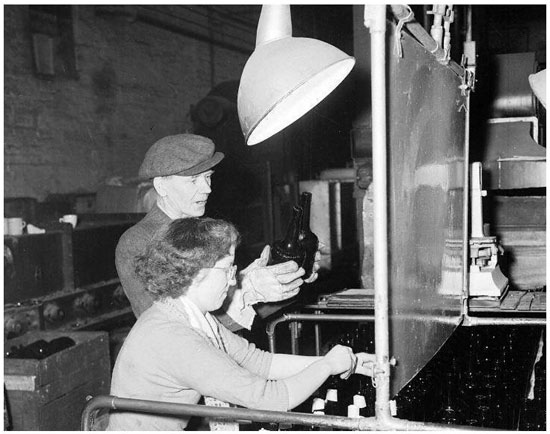

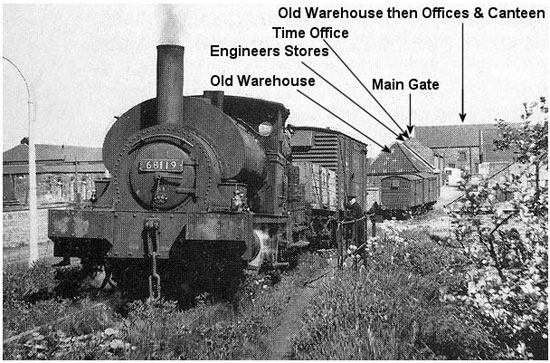

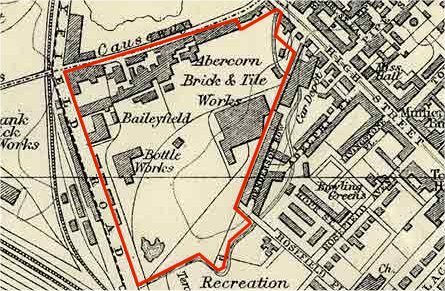

United Glass Ltd, Portobello, Edinburgh – Some recollections by Archie Young Jnr, works’ engineerBy Archie Young, United Glass Ltd (1962–1967)Edited by Christine HudsonMy late father Archibald (Archie) Young was a son of Portobello. He was born in Pipe Street, Portobello, in 1916. Around 1930, he started working at Wood’s Bottle Works (later taken over by United Glass Bottle Manufacturers) as a pallet maker. Thirty eight years, he was virtually the last man out of the gates in 1968, although there was a period of a year when he left to work at Queen Ann’s whiskey distillery. Following this brief sojourn, he worked at the United Glass distribution centre at Newbridge, Edinburgh. When my father was called up for the Second World War (1940), he was interviewed by the then work’s manager, who told him that on his return from the war he would be re-employed straight away. After the war, my father returned to United Glass, this time as a bottle sorter; this involved looking out for around 40 faults that could occur during manufacture – good eyesight was called for. In 1950, my dad introduced me to the factory. I was never more scared in all my life; the noise from the machines was terrific and then there was the heat from the furnaces: unbearable to say the least for a little boy of five years old. United Glass was very family oriented: there were quite a few sons and daughters who worked there as well as fathers and mothers. In 1953, I was taken very ill and rushed to hospital. I was in for two months, and when I was due to come out, the factory manager sent the work’s car to collect my mother and father, and take them to fetch me from the hospital; that’s how caring the people were. Around 1956, my father was promoted to supervisor of the bottle sorters. I can remember him working all hours; many a time he would work two shifts as he was so devoted to his work, and he loved every minute of it. Then, in 1960, he was promoted to sorter manager and training manager, running both posts at the same time. In about 1964, a young man came in from a university down in England, Manchester I think, to share my father’s position, which my father did not like. This young man eventually started to change the inspection rules. My father protested but was told to allow the young man to go ahead, but because of a huge mistake by this graduate, United Glass Portobello nearly closed down. He had allowed bottles through that were highly dangerous. The bottles were in the large warehouse when the problem came to light, and every bottle had to be rechecked; this was very time-consuming and cost a lot of money. When I went for an interview for second-year apprentice position, it was conducted by Chief Engineer Mr Cyril Langholm. I was asked a lot of questions then to do some drawings of machine parts. Eventually, after two hours, he informed me that I had the job and would be paid £5 per week; the job I held previously had only paid £2per week. I started with United Glass in 1962 as a second-year apprentice engineer fitter and turner. Mr Langholm was a brilliant engineer and a hard taskmaster, but fair if you did your work. There were then six apprentices on the engineering staff: myself, Alec Campbell (grandson of the early works manager Alec Campbell), Steven Murray, Brian Bissett, George Buchanan and George Smith (electrician). I remember walking through the main gate and being surrounded by very old buildings; the brickwork was a sort of reddish-brown colour. During the early months of working there, I explored the factory buildings. It felt wonderful just walking through the old buildings; it was like stepping back in time. I came across an old workshop at the top end of the factory where the Primrose furnace used to be. I can see it now, all the old engineering tools still hanging up on the walls just rusting away. There were two large boilers at the top end of the factory. These were manned 24 hours a day and produced the hot water for the whole factory. Just down from them was a 100-ft chimney: I think that was the last thing to be knocked down. A company called Alexander’s was given the demolition contract for the whole factory. Next to the mould shop was a paper and cardboard bailer that produced square blocks about 4-ft square. At the end of the factory, a new large warehouse was built with a sprinkler system fitted in case of fire. However, the problem in the warehouse was pigeons and seagulls: they cast their droppings on the boxes, so the boxes had to be replaced, which cost a lot of money. Someone came up with the idea of getting people in to shoot them with air guns, but every time they missed, they shot holes in the roof. This meant the rain got in and damaged the cardboard boxes, so the cycle of replacing them started again, and then the roof was repaired. It must have involved a lot of cash outlay. The tradesmen were all good men to work under. My first tradesman was Thomas (Tam) Anderson. Our foreman at the time was Harold (Harry) Terrace. He was a hard man in many ways, although as an engineer he was fantastic, he had spent time in the Merchant Navy as an engineer. Everyone in the factory mostly got on very well together; there were one or two that were a bit strange but we ignored them. The company had what was called a Scammell truck: it had a wooden cabin and a trailer. One day, when ice was bad on the roads, Jimmy Blues was driving along by Seafield road when the trailer started to jackknife: it came right round and completely shattered the cab. Jimmy was hurt and went to hospital; this was the last truck of its kind to be used by the factory. One day, Alec Campbell and I were told to go and check under the old Primrose furnace, which was not in use. I can’t remember why, but off we went with torches in hand. This was a round furnace, and from the floor to the base was only about 15 inches. Down on our stomachs we went and started to crawl through. The torches were not the best: the light was very poor. I saw a pair of eyes looking at me, and, thinking it was Alec, I spoke to him. He shouted, “I’m over here. Who are you talking to?” It turned out it was a big rat; we never got out of a situation as quickly as we did that day. There were two furnaces, No. 61 and 62. They were nearly square in shape, and were fired by oil burners, I forget how many. At times, the nozzles would choke up and it was the engineers’ job to remove the burner unit and clean it out. This was fairly hot work, as we had to go right up to the furnace to remove the unit. No. 62 was green glass I think. The fire bricks supporting the bottom of the furnaces eventually started to “rot”. It was the factory bricklayers’ job to replace them. They had to use a lance that fired compressed air, which they guided to remove the damaged bricks. It was my job to go down with them and connect the air supply. This was very hot work, and we had to wear heatproof suits and hats and visors. We were only allowed to work there for an hour; then we had to rest for an hour. During the rest period, we were supplied with a bottle of salt water by the nurse; she made sure everyone drank it. The taste was horrible at first but we got used to it eventually. The molten glass came out of what looked like a bath tub. It released what we called a single gob, which eased out of the tub and was cut it to length with a set of shears. This then dropped into an initial mould before it was transferred to a final mould. Pincers grabbed the finished bottle and transferred it to a chain conveyor. Then it was slid onto a right angle conveyor via a star wheel. A certain number of bottles was allowed past, and then a stacker bar placed the bottles into a lehr. This was used to anneal the glass; this took hours, about 10 I think, as it was very slow moving. The batch house was where the ingredients for the glass were mixed. Broken glass called cullet was fed into a sort of large cement mixer. It was huge. Then the chemist added all the powders that were needed. These ingredients were mixed together and transferred onto a conveyor belt, which travelled up to the furnace and tipped the mixture in. The mould shop was quite big; around 12 men worked there. It was divided into two shops. The damaged moulds went to No. 1 shop to be cast welded. It was normally the corners of the mould that were damaged, and a small weld did the trick. In this shop, two men also engraved the figures on the moulds, depending on the product. Then the moulds were transferred to No. 2 shop. Here, they were checked to see if they were warped, and they also had the cast weld ground down and polished to return the shape of the bottle. The works’ railway engines reversed trucks containing sand and chemicals into the yard. At one time in the early years of the glass works, the sand was brought up from the beach at Portobello by horse and cart. This had a very adverse effect on the beach and was stopped; the sand was brought in from elsewhere. One day in 1964, a lot of people were milling around just outside the gatehouse but inside the factory grounds. I saw my father and asked him what was going on. He told me that there was an old Roman drain under the ground and that they had brought in an old employee in his eighties to show them where to dig for it. Sure enough, under the spot he pointed out was the wooden drain. Also in 1964, we had a new chief engineer called Mathew (Matt) Young, no relation. He came from the west, probably Glasgow; he was small in stature but a really nice man. Mr Langholm then became the assistant factory manager. Pay day was on a Thursday but in 1965 it was changed to a Friday. Many men in the factory could not read or write; I was shocked at this. Here were grown men drawing their wages and placing their marks on the time card: each was different, some had a cross, others made tick marks and some drew ticks with lines through them. One man used to ask me to read the paper to him every lunch break; he was very grateful. The apprentices were urged to do projects. We had various individual projects, and the chief engineer would check them when they were complete. We had a big one that we shared: this was to rebuild an old three-wheeled Lister truck that had lain rotting in the yard for years. We had it up and running within four months; we had made many of the parts ourselves. It was gleaming. Mr William Bailey’s old house was the main office (Mr Bailey was the founder of the original glassworks on the site). It was a beautiful mansion to look at. It had a big car park. Sadly, it is all gone now even the house; the site is owned by a large car dealership. Education for the apprentices was at the Ramsey Technical Institute on Portobello Road, now made into flats; then in 1964 we transferred to the Napier College at Morningside, Edinburgh. When electric cables were to be laid at the works, they asked me to be a tunnel rat, as I was slim then. I went underground with a rope tied to my waist and crawled through the tunnel to the other end. Then we dragged the cables through. It was hot work underground, but I was paid 2/6d extra an hour for doing it; this made up for the sweat I lost! We had a wonderful football pitch known as Wood’s Park. We had our own football team called Portobello Primrose, the latter being the name of the old furnace. I played right back for the Primrose. In the summer, most of the top football teams such as Hearts, Rangers, Hibs, and Celtic to name a few, would play there in a knockout competition. We all got in free; I think the whole of Portobello was there watching. At the back of the pitch was where the factory kept the broken glass (cullet). This used to be the area of the “secret works”. Eventually the pile of cullet grew and grew to the extent that we could no longer play our games there. The “secret works” made various chemicals. What they were nobody knows except those who worked there. The building was known originally as the chemical works, but when Mr Arkley took over, there was absolutely no admittance to anyone who didn’t work in it. At the entrance to Wood’s Park was the United Glass Social Club. It was not fancy but it was a safe place to drink in; there were never any fights. The employees knew better; if they caused a problem, the factory manager would have a stern word with them. Around 1965, Carlsberg brought out lightweight bottles and we were given the contract. This new process involved a double gob of glass. At first it gave us a headache, but we soon had it up and running. The death knell for the glass bottle industry was the advent of plastic bottles. When the factory closed, I think around 300 people were laid off. We had a fantastic canteen, even outsiders were allowed to come in and have a meal. The canteen was immaculate, and the food was the best. About 1965, the factory had a shower room built with changing cubicles. The engineers were given two lockers, one called the “dirty locker” and the other the “clean locker”. I could go to work wearing a suit, and then change into my working gear. I completed my apprenticeship in 1965; when I left I was paid £13 per week. One day in September 1967 we found out that the factory was to close in December. Many a grown man cried that day. When the news was given to us, we were all numb with shock. United Glass called in the Employment Agency straight away; interviews were carried out, and other employment was offered. We were told that if we saw the closure through, we would get a week’s wages as a reward. Quite a few of us remained; I left, I think, the last Friday in December of that year. Mr Horace A. Basterfield, the last factory manager, was a true gentleman. He was slim and wore glasses, he also smoked a pipe. The way he walked around, anyone would have known that he was the overall manager. I heard a couple of years later that Portobello works should not have closed. Somewhere along the line it had been a typist’s error. They should have closed a factory down in England instead. My father was surprised at the closure, stating that the production targets they were given were well met. PHOTOGRAPHS

LIST OF ENGINEERSCyril Langholm (first Chief Engineer), Mathew Young (second Chief Engineer), Thomas Anderson (Fitter), John Boyd (Fitter), Harold Terrace (Foreman Fitter), Robert Jeffries (Fitter), Alec Campbell (Fitter), James White (Fitter), Andrew (Fitter) unknown last name, Steven Murray (Fitter), George Buchanan (Fitter), Brian Bissett (Fitter), Archibald Young (Fitter/Turner), John Hamilton (Fitter), George Milne (Fitter), Thomas Connelly (Fitter), Danny Dickson (Fitter), Charles Warren (Fitter), Fenwick Wilkinson (Turner), plus? three others whose names I can?t remember. ELECTRICIANSGeorge Flockhart (Foreman Electrician), Jimmy Simpson (Electrician), George Smith (Electrician) and Richard Beverage (Labourer) WELDERS/BLACKSMITHSAndrew Milroy (Blacksmith/Welder), George Falconer (Blacksmith/Welder), George Davis (Welder) and John Diegnan (Hammer man) BRICKLAYERSJames Kerr (Bricklayer), John Burns (Bricklayer) and George Brockie (Labourer) ©2009 Archie Young & Scotland's Glass See Also: Article on the works by H A Basterfield mentioned above here |

| ← The Portobello Factory (1966) |

|---|

| < Previous |

|---|

Joomla template created by Rosswerkz Studios