Information and History

| Glass articles - Scottish Glass General |

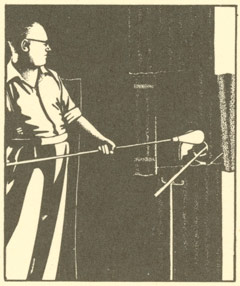

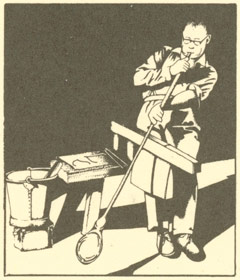

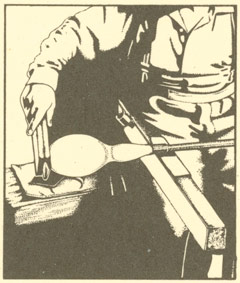

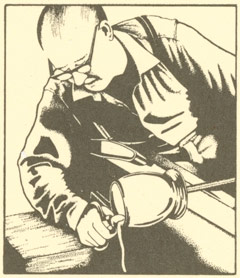

Edinburgh Crystaltext from 1977 Thos. Webb and EC Crystal Catalogue1. The Making of Crystal Glass2. The Decoration of Crystal Glass3. Characteristics of Crystal Glass(Glass-Study.com Notes 2008: Text was unnumbered pages between catalogue sections. The Edinburgh Crystal items are shown in the Scotland's Glass Catalogues. The remainder of text, Webb related and the entire catalogue are available only to Glass-Study.com members.) |

|

|

||||||||

|

| ← 2010 Conference | Jacobite glasses – Fascinating and controversial → |

|---|

| < Previous | Next > |

|---|

Joomla template created by Rosswerkz Studios